Angela Carter at the Movies – Daily Telegraph

Had Angela Carter lived she would have been 70 this week and it’s a fair bet she would have celebrated her birthday with a night at the movies. “I like anything that flickers,” she said, finding in cinema’s luminescent beings an image of her aesthetic sensibility, which was at war with the essential in art. She was an intellectually knowing writer, as certain of what she was up to as any novelist of her generation, often remarking that her fiction had “a tendency to be telling you something”. As she had designs on her readers, making them a participant audience – waiting for the next sleight of hand, the next trick of the light – so, from the beginning, she sensed that film had designs on her: “When I first started going to the cinema intensively in the late Fifties,” she wrote, “Hollywood had colonised the imagination of the entire world.” It fascinated her; she “resented it”; her cinema-going continued unabated.

By the Seventies her excursions to the pictures, often with gay friends like the novelist, Paul Bailey, were usually to London’s independent cinemas. She enjoyed visiting these tatty, rundown palaces and was a regular at the Little Bit Ritzy in Brixton when I worked there in the early Eighties, coming to see Tarkovsky’s The Mirror (1975), among other films. And I remember her talking about a visit to the Electric in Notting Hill Gate, recounting with relish how fleas jumped off the seats and patrons indulged in acts rather more intimate than the customary necking over popcorn in the back row.

The so-called “art houses” were a lot rowdier then. At the Ritzy, ancient projectors meant that films often broke down during the changeover from reel to reel, and a member of the audience might get up and play rock‘n’roll on the clapped-out piano at the side of the stage. It was a time when London thrived culturally. Many young people found it possible to live on the dole, work at cash-in-hand jobs and spend their free time writing, painting, making Super 8 movies or, like the drag queens squatting in Railton Road, working on the endless task of re-creating oneself.

I bumped into Angela wandering up Railton Road after the riots, delighted by the carnival spirit that prevailed in its aftermath, when the police temporarily withdrew. Raised in Balham, schooled in Streatham, taking her first job as a reporter on the Croydon Advertiser and later living in Clapham, she wasn’t just a tourist: she knew the streets of South London well. When Grace Paley came over from New York and we took her to Brixton market, Angela proudly showed her the best stalls for aki, salt fish and yams.

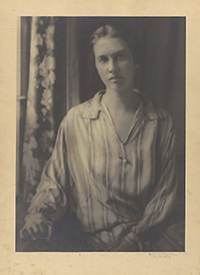

Angela Carter and Grace Paley on the tube to Brixton.

You can find these places in her swansong, Wise Children (1991): Bard’s Road, where the theatrical twins Dora and Nora Chance live, is in reality Shakespeare Road, running off Railton Road, or the Frontline as Brixtonians used to call it before the squats were knocked down or tarted up. In 2008 Lambeth Council named a new street after her, Angela Carter Close – a great “Yah, boo, sucks!” (one of her favourite comebacks) to the Booker judges who never gave her the prize.

From the beginning she wrote in praise of “recycling” and her fictions deploy the tricks of pantomime and music hall, those bawdy and popular arts that gave rise to the cinema (in turn, harking back to magic lanterns, fairy tales and oral storytelling), so she was inevitably drawn to film, a bastard medium based on refashioning the work of others. It appealed to her, too, as a collective art, not reliant on some master author. She was dismissive of post-war French intellectuals who tried in their auteur theory to trash the collectivity of the Hollywood system and raise the director to the status of sole creative genius.

French cinema itself, however, was a significant influence, particularly Godard who underscored the anti-intellectualism of British culture: “When Godard quoted Hegel, Lautréamont, Fanon, we didn’t groan. We pricked up our ears.” He made her see herself differently. She was not the product of F R Leavis and the welfare state – as Carter and a generation of grammar school children had been told they were – but part of “the great international conspiracy of the disaffected”, a child of Marx and Coca-Cola, “Hitchcock, Dostoevsky, Brecht – and of pulp fiction, phenomenology and the class struggle. Heady stuff, that changes you.”

Her favourite film was Marcel Carné’s Les Enfants du Paradis (1945): “It is the definitive film about romanticism… in which it always seems possible to jump through the screen… and live there, in a state of luminous anguish.” This fantasy of crossing over, and cinema’s state of longing, its ingrained nostalgia for somewhere else, is explored in Carter’s picaresque fantasy of the New World, The Passion of New Eve (1977), in which she charts the progress of a misogynist English man across America. Evelyn is castrated and transformed into Eve who, in turn, is impregnated by Tristessa, an ex-film star in the Garbo/Dietrich mould. As it often transpires in her fiction, the beautiful woman is a fake: Tristessa is in fact a man. “Enigma. Illusion. Woman?” Carter upbraids him/her, “And all you signified was false!”

At the centre of the book’s dark journey is the glass mausoleum to which Tristessa has retired and in which she now sits, endlessly replaying her movies, a witness to her own immortality. This labyrinthine house of mirrors is also a house of horror, a waxworks in which pale imitations of the Hollywood dead – Valentino, Harlow, Dean, Monroe – lie in transparent coffins. Carter, of course, throws stones at this glasshouse, sets it spinning and brings it shattering to the ground. But, as her friend, the critic Lorna Sage, observed, “this isn’t a straightforward piece of iconoclasm. The only way to write oneself out of the labyrinth… is to take the mirror-images seriously.” And it is, I think, as a writer who understood, and took the mirror-images seriously, long before others thought them worthy of thoughtful attention, that Carter will be remembered.

There are more cine-fables in American Ghosts and Old World Wonders, published posthumously in 1993, the collection was influenced by Robert Coover’s A Night at the Movies (1987). These stories are like Late Show re-runs laced through Carter’s private projector, they Play It Again but off-kilter. There is a piece in praise of Jan Svankmajer’s semi-animated version of Alice in Wonderland, a wonderfully sadistic tale, ‘Gun for the Devil’, set in Mexico – it’s a tortilla rather than a spaghetti Western, and a script replaying John Ford’s Jacobean melodrama, Tis Pity She’s a Whore, as the latter-day John Ford, the director of Stagecoach (1939), might have filmed it.

Her peroration, containing Carter’s most playful writing on film, is the ‘The Merchant of Shadows’. This is the tale of an English student in America, working on a thesis about Heinrich Mannheim, a German émigré who changed his name to Hank Mann and became a film director in Hollywood, only to commit suicide in the dark days of 1940. The story begins with a disorienting anomaly. Our English hero recollects when he first saw the sign announcing HOLLYWOODLAND and we assume the story is set in the past, because the part that says LAND has long since crumbled like old film stock and fallen into the valley below. A moment later, though, we are informed he is visiting Mann’s widow. Outside her mansion is a “crap-caked Toyota” – so we must be in modern-day Los Angeles, furnished now not by the imaginations of European immigrants but by Asian hardware and finance. This time-bending trick is just one of many vertiginous moments Carter achieves through narrative twists but also by stylistic effect. The writing here is pathetic fallacy played as camp, the California landscape , flooded with cinematic meaning: “The ocean shushed and tittered, like an audience when the lights dim before the main feature.”

Among the pleasures of the story is the feeling of being goaded, Carter prods you on to work out the mystery. So, you think, Hank Mann is clearly not Anthony Mann, director of Westerns, more likely he’s some hybrid of Erich von Stroheim – the famously sadistic director Carter reprised in Wise Children, lover of the casting couch and “steak-eating orchids”; Josef von Sternberg – who directed Dietrich in The Blue Angel (1930), the German precursor of endless cross-dressing turns in Hollywood; and Heinrich Mann, of course – who wrote Professor Unrat (1905), on which that film was based, and who himself washed up in California in 1940 with what was left of Germany’s intelligentsia. (In life, the wife, not the writer, committed suicide.)

The name, Mann, announces what is hidden from the hapless student who, blinded by scholarly earnestness, is unable to read between the lines, to see the joke, until it is literally shoved under his nose at the end of this sensationally tall tale. He suspects something is wrong. The setting of the cliff-top mansion to which he has been summoned is overgrown and decaying; a gin bottle floats in the obligatory Hollywood pool. Our hero is reminded not only that this is the very pool in which Hank Mann expired, doing “his A Star is Born bit”, but it recalls, ominously, the pool in Sunset Boulevard (1950). When the director’s widow, once a famous star, is finally wheeled out, she is bewigged, painted and pancaked to the hilt. He finds himself playing the role of gigolo to her impersonation of Gloria Swanson’s bitch-goddess.

Thinking back over her career he surmises, “She was no Gish, nor Brooks, nor Dietrich, nor Garbo, who all share…the ability to reveal otherness.” And perhaps he’s right. For hers is not the ethereal otherness of the film star. But like Red Ridinghood in ‘The Company of Wolves’, (a story Carter and Neil Jordan adapted for the screen), our innocent abroad still cannot see that “the wolf may be more than he seems”. Recklessly he passes over the one clue his research presents him with. Tracking down Mann’s second wife, once a starlet, now a dyspeptic cleaning lady, he refuses to fork out the hundred bucks she asks for a snap of the director “artfully posed” in schoolgirl uniform, on the grounds that, “it wouldn’t add much to the history of film.”

He is wrong, of course, spectacularly so, for as it turns out, Mann hasn’t died, just moved on, and his taste for transfiguration – revealed in the photograph – gives the clue. Meanwhile Mann’s widow, the real star, has, like Garbo, wearied of the limelight, and taken to playing the sidekick, leaving the stage to Mann himself. “Having made her,” Carter tells us, “he then became her, became a better she than she herself had ever been”. For the knowing reader, there was an early sign secreted in the story: the student described his meeting at the mansion as a “tryst”, suggesting to the reader paying attention, that this would be another Tristessa-like story, another tale of revamped movie stars.

It was not just that Carter was well-versed in Hollywood’s famously camp moments: Garbo epitomising androgynous beauty in Queen Christina (1933); Hepburn hamming it up as a travelling transvestite in Sylvia Scarlett (1935); Dietrich in top hat and tails flirting with the girls in Morocco (1930) and Blonde Venus (1932). The point she makes here is that Hollywood brought about the final denaturing of femininity in Western civilization because its eroticism was built upon the allure of the fake. The movie stars who inspired Tristessa were so manifestly queens of artifice, creatures of dream and design, they flaunted an idea only previously rumoured in books: that femininity itself was a drag act.

What would Carter make today of Della Grace’s self-portraits, with her breasts and moustache; Cindy Sherman in her various (dis)guises from slut to Ancient Master; the swaddled creations of Alexander McQueen and Lady Gaga; the androgynous beauty of Cillian Murphy in Breakfast on Pluto (2005) or Hilary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry (1999)? No doubt she’d have some new angle on it all, but as one obituarist lamented: “She will never have the chance to shock us at 70.” She is not here to deliver her discerning commentaries, so we must do the best we can by continuing to read this most undeceived of writers, attending to her iconoclasm, wit and soaring imagination.

This is an extended version of a tribute to Angela Carter that appeared on 3.5.2010 in the Daily Telegraph and on the paper’s website as ‘Angela Carter Remembered‘.