Jamal Mahjoub Interview: AKA Parker Bilal – Al Jazeera

Salman Rushdie once observed that migration was the “most common experience of the twentieth century”, but this, in the main, involved movement from one country to another. In the twenty-first century it looks as if more and more of us will have peripatetic lives. Ineluctably, despite pockets of resistance, we are becoming more mobile and mixed. Jamal Mahjoub is one of a new group of writers who personify this condition. His interests, tastes and understanding of power are all influenced by being part of the diaspora. But unlike his father who was exiled from his home in Sudan, Mahjoub is of a generation of willing travellers, nomads constantly in search of new chances and other ways of thinking or being.

Of English and Sudanese descent, Mahjoub has, so far, lived in London, Liverpool, Khartoum, South Wales, Sheffield, Aarhus, Cairo and Barcelona. His wandering has given birth to a prolific body of work: seven books of literary fiction under his own name, and three crime novels as “Parker Bilal”, the latest of which, The Ghost Runner, has just been published. This pseudonym, made from the names of his grandfathers – a Nubian boatman on the Nile, and a German refugee in England who anglicised his name – celebrates his disparate inheritance. But there are dilemmas raised by such diversity. During his recent visit to London, I asked Mahjoub if anyone ever questioned his authenticity or right to speak? “That’s exactly the position a writer like myself is in. Because you don’t have a people behind you and are not speaking from within an established voice – whether that is national or literary – you question: what tradition do I belong to? I don’t think many people would include me as a British writer. Do you include me as a Sudanese writer? Well no, not really, because I don’t write in Arabic.”

Many of his novels explore this conundrum, often through loosely autobiographical stories, though he is not interested in himself so much as the way in which someone like him, roaming through Africa and Europe, makes sense of the world, and brings new meaning to it. “Books, to my mind, are, by definition, about other people: I don’t write specifically to know about me, I certainly don’t write to justify me. I write about things that fascinate me about the world, to understand other people and perspectives.” When he tells me that he’s currently reading Karl Ove Knausgård in Danish (he lived in Denmark for a decade), I wonder what he makes of this writer who became a global literary sensation with a six-volume study of himself? “It’s very Scandinavian. What strikes you about Scandinavia is that it makes people independent from an early age. Your rights as an individual mean that you can afford an apartment for yourself, you get subsidy from the state. You have a right to vote, but many people don’t exercise that right. There’s a lot of cynicism and a huge amount of self-absorption. They have all these tremendous opportunities and yet it’s all geared to making things more comfortable for the individual, not about changing the world or caring for others.”

When I ask him if a novel can change the world, his answer is both sceptical and passionate: “No, I don’t think so. I do believe, though, that at some point culture can change things. A lot of the popular sentiment for black South Africa was encouraged by Paul Simon’s album, Graceland, even though it was criticized at the time [for breaking the boycott of Apartheid goods]. People listened to that record who had never listened to African musicians before and that changed their perception. It had a huge influence. Do we really change the world? No. But I think we have to try.”

The variety of Mahjoub’s writing makes him hard to categorize. All of it, though, is characterized by intellectual restlessness, and much concerns the tension between modernity and tradition. The first three novels comprise a trilogy about Sudan. He looks at the late twentieth century nation, divided between desert people and city-dwellers trying to become part of the contemporary world; then the pan-African period through the eyes of an exile in postwar France; and finally, Sudan’s failed struggle for independence at the end of the nineteenth century. The Carrier draws on Mahjoub’s training as a geologist and shifts back and forth between the present day and the Enlightenment, between Algeria, Spain and Denmark. Nubian Indigo is about the raising of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s and its impact on the ancient people and culture it displaced. Then there are two novels about mixed-race families: Travelling with Djinns, in which a father and son take a road trip (“Europe is my dark continent, and I am searching for the heart of it”), and The Drift Latitudes, tracing one family through the twentieth century, by way of a German U-boat, a Liverpool jazz club, and a garden in Sudan.

Perhaps another reason for Mahjoub’s abundant output is his sense that the complex subjects he’s addressing are likely to be met with bias, and finding the voice in which to express them is mired with difficulty – so you have to keep making the attempt from new angles. In Travelling with Djinns, the main character is attacked on all sides for misrepresenting Sudan. In his own life, Mahjoub has had similar experiences: “Because my first novel about Khartoum is quite critical, the people who liked it were old communist friends of my father and radical political activists who had spent time in prison: they thought it should have been more critical. Many of the middle class, comfortable Sudanese, though, wanted a more complimentary portrait. But, for me, at that age, the purpose of writing was to change the world, to make people aware of what had happened, because I felt, strongly, that Sudan had become this wasted opportunity. There were so many things that could have gone right that had gone wrong, and blaming the British and the colonial era was just not enough anymore.”

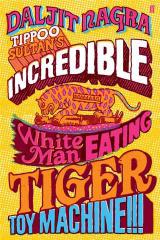

If there were those among his acquaintances who disapproved of his books, literary critics have been united in their praise. But, as often happens with writers who can’t be packaged in easily marketable categories, Mahjoub’s publishers failed to propel him into the limelight. So he has opened a second strand in his career. With the Parker Bilal series, his aim is to write detective novels for half the year and earn enough to finance the “Jamal” books he concentrates on the rest of the time – which is not to say that writing crime fiction is a compromise. He’s been a fan of the genre since childhood, finding Sherlock Holmes’s estrangement, or Conan Doyle’s mysteries, more hospitable than much literary fiction: “Writers such as Ian McEwan or Martin Amis”, he wrote recently, “describe worlds that were keenly defined as places where someone like myself simply would not fit in.” Unsurprisingly, then, his own detective, Makana, is also a precarious figure, having fled from hard-line Islamists in Sudan only to encounter another round of bullies and tyrants in Egypt.

“Ever since I’d first gone to Cairo [after his family were exiled there in 1989], I had wanted to write about this fascinating place, a vast city full of amazing history and a modernity which is completely skewed. It felt then like Paris just before the revolution: you had tremendous poverty on the streets and this wealthy class who were almost hermetically sealed off.” Into this world, Mahjoub brings Makana, a man, like Cairo itself, poised between the old and the new: “He is modern in his outlook, not fazed by women taking part in society and being able to move around freely. But he’s also old-fashioned in his chivalry, duty and dedication to the truth.” It is Makana’s liminal status as an exile that makes him such an adept navigator of the city, able to fade into the background because nobody pays attention to an African migrant. But when someone is needed to investigate a problem, being an outsider makes him highly employable: the system in Egypt is so corrupt that no one trusts the authorities.

Alongside the Makana series (seven more are planned, running as far as the revolution in 2011), Mahjoub is working on a novel about England in the 1980s. He wants to explore the alienation he felt as a young man, newly arrived in the country, mixed with the heady excitement of a culture that, briefly, seemed to embrace everyone: in the music of Two-Tone and Rock Against Racism, the books of Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy, and in films such as Hanif Kureishi’s My Beautiful Launderette. This moment of solidarity ended, he feels, with the fatwa against Rushdie: the umbrella community was shattered as the global divide between East and West came to dominate even parochial politics.

Mahjoub is also writing a non-fiction book about Sudan, which he hopes will encapsulate many of his earlier themes in a Sebaldian mix of memory, reflection and philosophy: “It’s a form that I like: creative non-fiction that allows the imagination in.” His expectations for this new work may not be as world-changing as those he cherished for his first novel, but he continues to have faith that his writing can extend our understanding: “It is the presence of your voice which changes the balance of the way people see the world. Without you being there, the cultural horizon that people have will be less. It will be Martin Amis.”

This is the original version an an article that appeared on Al Jazeera’s website on 23.5.2014 as ‘Jamal Mahjoub: novelist, nomad and not Martin Amis‘.