‘Seriously Funny: Angela Carter’s Wise Children’ – Virago 1992, 2007; Macmillan 2000; British Library 2016

This essay was first published not long after Angela Carter’s death in 1992, in Flesh and the Mirror: Essays on the Art of Angela Carter – a book edited by the woman Carter once told me was her “best friend”, certainly her strongest critic, Lorna Sage. In 2000, it was included in Angela Carter: Contemporary Critical Essays, edited by Alison Easton for Macmillan. Virago re-published it in 2007, in an updated edition of their book with a new Introduction by Ali Smith – one of a young generation of novelists who claim Carter as an influence. For this edition Virago inverted Sage’s title to Essays on the Art of Angela Carter: Flesh and the Mirror. In May 2016, a shorter version of the essay was included on the British Library website, Discovering Literature: Twentieth Century, under the title ‘Shakespeare and Carnival in Angela Carter’s Wise Children’.

This is the original version.

1. INTRODUCTION: CRISSCROSS

I’m sure Angela Carter would have been pleased to hear that the hottest thing in pop music these days are two young mixed-race American rappers who wear their trousers back to front and call themselves ‘Kriss Kross’. Carter’s last work of fiction, Wise Children – in the spirit of the novel one could call it, perhaps, an old bird’s eye/I view of the social, cultural, imperial and sartorial history of the century now ending – is itself patterned with intersecting tracks and grooves that are made by her characters ‘crossing, criss-crossing’ the globe, by the zigzagging lines of familial and artistic descent that reaches across and into their lives; and by the writing itself, which passes through – often parodying – many genres and styles, yet remaining something completely authentic and its own.

2. FAMILY AND CULTURE: TWIN PEAKS

Wise Children is the story of ‘the imperial Hazard dynasty that bestrode the British theatre like a colossus for a century and a half’, and its bastard progeny, Dora and Nora Chance, identical twin girls who are illegitimate twice over: by birth, because their father, Melchior Hazard, denies his paternity of them time after time, and by profession, where, as a novelty act, they dance the boards in music hall, appear briefly as extras in an ill-fated Hollywood musical, and finally undress (though never beyond the G-string) in seedy postwar strip show like ‘Nudes Ahoy!’ and ‘Nudes of the World’.

The story is told by one of these lovely bastards, Dora, the wise-cracking, left-handed southside twin sister who rakes over more than a century of family romance and history. As in all the best modern fiction, the action takes place in just one day. A special day, however: it is the anniversary of Shakespeare’s birthday, which happens also to be Dora’s and Nora’s own – this year their seventy-fifth. It is the birthday and centenary, too, of another set of twins, Melchior and Peregrine Hazard, father and uncle (but which is which?) of these performing sisters, ‘The Lucky Chances’. The double-faced Hazard/Chance family is served up to the reader as a model for Britain and Britishness, obsessively dividing itself into upper and working class, high and low culture. And just as Dora proves these strict lines of demarcation to be false within her own family, so, too, her story shows the reader how badly they fit the complexity and hybridity of British society and culture.

It is relatively easy (and Carter has a lot of fun doing this) to show how we foster and exploit binary oppositions in culture in order to justify the domination and exclusion of others, and to sustain elite privilege in society, it is a much more complicated thing to respond to the fiction, the romances – family and otherwise – which we have built upon the idea of legitimacy and illegitimacy. Master of the dialectic is William Shakespeare, whose ‘huge overarching intellectual glory’ dominates the English literary canon and whose work, like Carter’s own, is brimful with ideas of doubleness, artificiality and parody. In Wise Children Carter not only weaves Shakespeare’s stories in and out of her own, she also reminds us of the extent to which his words and ideas impregnate English culture and life: his face is on the £20 note that Dora doles out to the fallen comic, Gorgeous George; and contemporary television programmes that poach their names from him like The Darling Buds of May, May to September and To the Manor Born, all make pointed, if somewhat disguised appearances in the novel.

Part of what attracts Carter to Shakespeare is his playing out of the magnetic relationship of attraction and repulsion that exists between the legitimate and illegitimate, between energy and order. This occurs most famously, perhaps, in the sliding friendship of Prince Hal and Falstaff. Near the close of her story, Dora tries to reimagine one of Shakespeare’s cruellest moments: what if Hal, on becoming king, had not rejected Falstaff, but dug him in the ribs and offered him a job instead? What if order was permanently rejected, and we lived life as a perpetual carnival? These questions are not answered directly (and I will return to her implied answers later), but this challenge to order, to the legitimate world, is made throughout the novel. When Dora describes Nora’s first sexual experience, she warns the reader not to:

run away with the idea that it was a squalid, furtive miserable thing, to make love for the first time on a cold night in a back alley with a married man with strong drink on his breath. He was the one she wanted, warts and all, she would have him, by hook or by crook. She had a passion to know about Life, all its dirty corners, and this is how she started…(p.81)

Wise Children, then, not only challenges legitimacy, it is also a celebration of the vitality of otherness. Paradoxically, though, because the legitimate and illegitimate world rely upon one another’s mirror-image of difference through which to define themselves, such a celebration of illegitimacy necessarily implies a valorisation of the system which produces outcasts. Knowing this, one of the questions Carter asks us in the novel is: what, then, should a wise child do? Revel in wrong-sidedness and, therefore, the system that produces it, or jettison the culture of dualism altogether? In answer, Carter’s wise – though now somewhat wizened – child, Dora, pulls off the sort of conjuring trick that her Falstaffian Uncle Perry is famous for: she manages both to have her cake and eat it, to revel in her wrong-sidedness, to sustain her opposition to authority, and yet to show that the culture and society she inhabits is not one of rigid demarcation, but has always been mixed up and hybrid: Shakespeare may have become the very symbol of legitimate culture, but his work is characterised by bastardy, multiplicity and incest; the Hazard dynasty may represent propriety and tradition but they, too, are an endlessly orphaned, errant and promiscuous bunch.

3. CULTURE AND IMPERIALISM

(i) ‘High’ Culture: William’s Word

The Hazard family is a patriarchal institution, but its father figures (Ranulph and later his son, Melchior) find their authority deriving not from God, but from a Shakespeare who has come to seem omnipotent in the hegemony of British culture, to embody not only artistic feeling but religious and national spirit too: for Ranulph, ‘Shakespeare was a kind of God…It was as good as idolatry. He thought the whole of human life was there.’ By becoming, each in his own generation, the ‘greatest living Shakespearian’, Ranulph and then Melchior assume a kingly status themselves. Having so often rehearsed the role of Shakespearian prince or king, these actors take on the mantle of royalty itself: ‘the Hazards belonged to everyone. They were a national treasure.’

At a late stage in the family’s history, mirroring the collapse both of empire and royalty, the imbrications of ‘The Royal Family of theatre’ make them appear as vulgar and commercial as our latter-day House of Windsor. Like them, the Hazard dynasty becomes national sport, soap opera masquerading as news. But in earlier times this regal troupe of players are not only commodities for the country (‘national treasure’), they are agents of Britain’s colonial ambition. Before the fall of the House of Hazard, Ranulph’s evangelical zeal for spreading the Word of Shakespeare is so great that he ‘crosses, crisscrosses’ the globe, travelling ‘to the ends of the empire’ in his efforts to sell the religion of Shakespeare and the English values he represents:

Ranulph. He was half mad and thought he had a Call. Now he saw the entire world as his mission field…[in] the family tradition of proselytizing…the old man was seized with the most imperative desire, to go on spreading the Word overseas. (p.17)

In Tasmania, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Montreal, Toronto, Alberta and even Gun Barrel, North Dakato, Ranulph Hazard’s travelling theatre troupe meet in their audience a passion for self-fashioning as great as Shakespeare’s own. As a consequence, they leave in their wake around the globe a string of towns called Hazard.

Throughout Wise Children Carter celebrates the vital and carnivalesque in life. ‘What a joy it is to dance and sing!’ is Dora’s refrain, but she is aware of the effect that the enthusiasm and self-absorption of carnival can have upon others: aware, too, of the ways in which power can be harnessed by a dominant group and brought to bear upon a weaker one. So she celebrates the craziness, ‘a kind of madness’, that drives old Ranulph to travel the world taking Englishness to foreigners, yet deftly shows how intimately connected are Shakespeare’s cultural domination and British imperialism.

Carter’s connecting of art and religion reinforces this idea: Ranulph sees it as his ‘mission’ in life to perform Shakespeare throughout the world in order to persuade other people of the greatness of the Bard’s words, just as missionaries took the Bible and tried to persuade ‘natives’ of the truth of God’s Word. Ranulph Hazard’s theatre troupe literally follow in the steps of religious evangelicalism – his ‘patched and ravaged tent went up in the spaces vacated by travelling evangelicals’. They perform in ‘wild, strange and various places’, and their costumes are ‘begged or improvised or patched and darned.’ Cultural hegemony may have been an important part of the imperial vision, but acting, Carter reminds us, has always been an illegitimate profession: peripatetic, thrown-together, made-up and sexually ambivalent – in Central Park, Estella plays Hamlet in drag. Theatre, and particularly the theatre of Shakespeare, has played its role in colonising the minds of other countries, but it is also a potentially destabilising and subversive force.

(ii) ‘Low’ Culture: Gorgeous George

‘Tragedy, eternally more class than comedy,’ sighs Dora, meaning both that it has a classier pedigree than comedy and is associated with the classes rather than the masses. Carter’s qualification, however, points to her conviction that, like everything else in life, art form (choosing to write comedy rather than tragedy) is a question of politics. ‘Comedy is tragedy that happens to other people,’ she says (taking in the process, perhaps, a swipe at Martin Amis whose comedies often are).

Dora first encounters the comic Gorgeous George when she is thirteen, entertaining the masses on Brighton pier. Uncle Perry arrives unexpectedly in Brixton with a carload of good things to eat and drink, and packs the ersatz Chance family (Dora and Nora, Grandma and one of Perry’s many foundlings, ‘Our Cyn’) off to Brighton for the day. There they find George, a combination of Max Miller, Frankie Howard (‘Filthy minds, some of you have’) and Larry Grayson (’Say no more’), he comes in the tradition of the holiday camp entertainer and his jokes are endlessly insinuating, every phrase or object carrying with it some double, sexual meaning. Sex is everywhere and with it, therefore, the possibility of incest. Reflecting England’s fallen status, George’s jokes mock ideas of strength and purity, and fuel paternal anxiety about redundancy and impotency. His comedy is parodic and slippery and perfectly timed, and his punchline, when it’s finally delivered, is a withering attack on a foolishly deluded old patriarch who thinks himself the greatest stud around: the son, taken in by his father’s boasts of promiscuity, becomes worried about committing incest with some unknown bastard offspring, but his mother tells him not to worry because, after all, ‘E’s not you father.’ B-bum!

George’s final coup de grâce, after singing ‘Rose of England’, ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, ‘God Save the King’, and ‘Rule Britannia’, is to strip off before his dazzled audience and reveal a torso tattooed with a map of the world: ‘George was not a comic at all but an enormous statement.’ But even a statement as blatant as the pink- (for British colonies) dominated world (Dora smartly picks out Ireland, South Africa and the Falkland Islands) emblazoned across the body of this latter-day St George is fraught with ambiguity. Unlike St George of old, Gorgeous George no longer wins battles and rules the waves; he merely represents the idea of conquest. He is a walking metaphor, an effete mirror-image. George shows us an empire falling; having once dominated the world, this Englishman can now be master of only one space: his own body.

George’s decline, like the British Empire’s, continues apace. Dora encounters him once more as an anachronistic Bottom (his kind of peculiarly English comedy doesn’t travel) in the Hollywood production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a debacle over which Melchior presides, and in which she and Nora have bit parts (they play Mustardseed and Peaseblossom). Finally, back in London, George ends up hitting rock bottom: Dora, catching a glimpse of his pink tattoo, recognises him in the pathetic street beggar who approaches her for the price of a cup of tea.

(iii) Fallen

If Shakespeare provides English literary culture with a model for plurality, it is in Milton, particularly in Paradise Lost, that we find a model for dualism in the world, a dualism resulting from the patriarchal and monistic vision of Christianity. One of Dora’s refrains (she has a few up her sleeve) is the Miltonic phrase, ‘Lo, how the mighty are fallen’, which is both a silly semantic joke and a serious intimation of the world she inhabits. Many of the descriptions of fallenness in Wise Children are specifically Miltonic or Christian: for instance, both Melchior and Peregrine are figured as Godlike and Satanic. Peregrine lands into the lives of the naked, innocent, unselfconscious and therefore Eve-like Nora and Dora as Adam arrived on earth: out of nowhere. And it is of Adam that Dora thinks when she sees him, because this is to be her First Man, the man who, like the fallen angel Lucifer, will first seduce her. In the same way Melchior, ‘our father’ who ‘did not live in heaven’ but who, God-like, is worshipped by the girls from afar, is also given a Satanic side: he appears ‘tall, dark and handsome’ with ‘knicker-shifting’ eyes, dressed in ‘a black evening cape with a scarlet lining’. Later he is Count Dracula (a late-nineteenth-century Satanic pretender), ordering Dora and Nora to carry dirt over from Stratford – as Dracula had carried it from Transylvania – to scatter on the Hollywood set of his film of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

In Hollywood, the English colony represents a parody version of the once great Empire, playing Disraeli, Queen Victoria and Florence Nightingale. Just as in Ranulph’s generation English theatre was shown to embody the nation’s imperial strength, so now the film industry in Hollywood symbolises America’s new role as a world power. Melchior’s attempt to produce a film version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is his way of trying to conquer Hollywood, ‘his chance to take North America back for England, Shakespeare and St George.’ But the trip to Hollywood is presaged by the burning down of Melchior’s manor house, and with the English theatre symbolically erased in the fire, ‘the final degeneration of the House of Hazard’ ensues. Ultimately we find Melchior’s son Tristram, the ‘weak but charming, game-show presenter and television personality, last gasp of the imperial Hazard dynasty’, presiding over an S/M game show.

(iv) The End

The sense of limitless freedom that I, as a woman, sometimes feel is that of a new kind of being. Because I simply could not have existed as I am, in any other preceding time or place. I am the product of an advanced industrialised, post-imperial country in decline.

It is typical of Carter that unlike many modernist writers she sees in the decline of empire – to adapt Brecht – not the death of bad old things but the birth of good new ones – her own liberation, for instance. Symbolising the newness that the death of the old might now bring into being, Wise Children is scattered with what Salman Rushdie, in a short story, called ‘the eggs of love’ . Dora’s and Nora’s bottoms jiggle like hard-boiled eggs; there are dried eggs during the war and smuggled black-market ones; Scotch eggs that landladies put out for supper; and in the snow, Dora sees egg-shaped depressions.

This is a cuspy, millennial novel, and ‘millennia’, Carter believes, ‘always gets strange towards the end’. Part of Wise Children’s strangeness is due, perhaps, to the disconcerting sense of beginnings and possibility at the moment of ending, of death. The story’s finale has a riotous celebration for the now-centenarian Melchior and Peregrine, after which Dora (who, at seventy-five has herself been thinking about calling it a day), finds that she and Nora have suddenly had motherhood thrust upon them. They toddle home – these unmarried, non-biological and overage mothers – ‘Drunk in charge of a baby carriage’.

Death has a strong presence in this book – not just the end of empire or the death of the patriarch, which Dora is happy to let go – but a sense of the presence of death in the midst of life. Dora is someone who wrestles with this, a spirited fighter who refuses to grieve for long, or give in to defeat. ‘Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery’, our autodidact narrator recites from Jane Austen. Dora’s optimism derives from both a moral and a political sense of duty learned at her grandma’s knee, whose often-recited maxim, ‘Hope for the best, expect the worst’ lies on the map somewhere between Gramsci’s ‘Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will’ and St Augustine’s ‘ Don’t presume, don’t despair’. Neither she nor Nora sheds a tear at the news of their beloved Tiffany’s death, though both are heartbroken by it. ‘Life must go on,’ says Nora, refusing to be engulfed by despair.

One of Wise Children’s characteristic inversions of the supposed order of life is that no one dies of old age, all are ‘untimely’ deaths – the only ‘true tragedy’, Dora says wisely: Grandma, hit by a flying bomb on her way to the off-license; Cyn’s husband, killed in North Africa in the war, and Cyn herself succumbing to the Asian flu of ’49 (the cat to the cat flu of ’51); Dora’s lover, Irish, makes his last exit in Hollywood caused by too much booze and a ‘dicky-ticker’; finally there is the apparent suicide of their godchild, the young, mixed-race Tiff, who, Ophelia-like, seems to have made her suicide a watery one, into the bosom of Old Father Thames. But this is just one of the instances in which – to use Edward Said’s phrase – Carter ‘writes back’. Her Ophelia does not give in to patriarchal abuse (by committing suicide in Father Thames): like Carter she, too, imagines herself as ‘a new kind of being’, and in the end it is she (the illegitimate outsider) who lays down the new rules of play for the Hazard dynasty.

4. A LOOKING-GLASS WORLD

(i) Pluralism and Difference

In Wise Children, Carter is able to suggest a jumbled, impure multi-culture, while showing clearly that class, racial and sexual elites which seek to exclude otherness are still a powerful and conditioning force. A reader of Foucault, Carter fully understood the way in which the dualistic structures that belong to the dying past – to Christianity, patriarchy and empire – are still extant in the present. By showing Shakespeare at the heart of English culture, as the ‘author of our being’, father to both the Hazards and the Chances (legitimate and illegitimate share his birthday), Carter is arguing that plurality and hybridity are not simply conditions of modernity, products of its wreckage, but have always existed and are characteristic of life itself. From this it follows that she does not see in plurality, as many postmodernists do, a nihilistic loss of value; rather, an existential acceptance of the facts of life and death in which contradictions are a sign of hope, and difference has to be negotiated rather than fought over as if there were only one place of rightness, one correct way of living that must be identically reproduced the whole world over. This is something that Dora’s grandma knows innately – feels it, as Dora does, ‘in her ancient water’. When, in wartime, she waves her stick in the air at the bombers overhead, she recognises that war is a result of patriarchal insistence upon monism: men fight to wipe out women and children (whom ‘she knew they hated…worst of all’ – because they are most other); but forever locked in some recidivist oedipal struggle, they fight, as well, to stop younger men stealing their thunder, to stop them taking away their distinguished mantles of poet or god.

(ii) Glasshouse Fun

But while men continue to fight wars, to battle for absolute control of land or language, Carter tells us we live now in a world of endless refraction. The days when a looking-glass reflected just one wicked witch, one absolute image of otherness, are gone. Now we have cinema, television, radio and video splintering the world ‘in a gallery of mirrors’ , a glasshouse of perpetual reproduction. Our relationship to these multiple, often contradictory reflections, especially for women, is as important and as determining as our relationship to other people. It is this awareness, critics like Lorna Sage have argued, that defines much of Carter’s work and makes it unique.

In Wise Children, however, the glasshouse is not the house of horror, the bloody chamber we have peered into with Carter so often in the past. These characters are not the glassy, fragile forms of some of her reworked fairy stories, eternally caged by images not of their own making. Dora’s narrative is a much freer, bouncier one, with a resilience that comes from a new kind of resourcefulness. Perhaps we have now lived long enough with our own shadow selves, Carter seems to be suggesting, that we are at last learning how to gain some control over them. Dora is a toughie, a survivor and a canny self-observer, and is not imprisoned by her female sexuality or the multitude of images of femininity that surround her. Rather, she seems like one of Shakespeare’s bastards, Edmund, determined not to let the Dionysian wheel of fate settle her life, but to find in the chance of her wrong-sidedness neither shame nor restraint, but opportunity. Because of this Dora is able to enjoy her own body, and the bodies of other women too. Maybe one of the meanings of the twins is a rather Laingian one: the idea that one need not be afraid of one’s image, but should embrace it, love it instead. Like the autoerotic Dora and Nora, one can ‘feast’ on oneself. (However, this enlightening idea finds it dark equation on the Hazard side, where the family seal is of an animal devouring itself – a pelican pecking at its own breast. This is because in a value system that is monistic, self-love – as I suggested above in the case of Ranulph and Melchior – inevitably implies incest or its correlative, cannibalism.)

5. FAMILY VALUES AND FAMILY SECRETS

‘Dread and delight coursed through my veins. I thought, what have I done..’ Perhaps part of the reason for Dora’s dread and delight when she momentarily wonders whether, as a young girl, she had fucked her Uncle Perry, has to do with the idea of gaining power not with a man’s weapon – his strength; but with a woman’s – her sex. One way for Dora, the outsider, to gain access to power and legitimacy of ‘the House of Hazard’ is to fuck her way inside, or at least to bring it to its knees by transgressing its laws of order and hierarchy: uncles are not supposed to have sex with their nieces, particularly when they are only thirteen – Dora’s age, it finally transpires, when Peregrine first seduced her.

Wise Children is like the proverbial Freudian nightmare aided and abetted (as Freud was himself) by Shakespearian example. Dora’s family story is crammed with incestuous love and oedipal hatred: there are sexual relationships between parent and child (where this is not technically so, actor-parents marry their theatrical offspring – in two generations of Hazards, Lears marry Cordelias); and between sister and brother (Melchior’s children Saskia and Tristram). And there is oedipal hatred between child and parent (Saskia twice tries to poison her father, and she and her twin sister Imogen are guilty of either pushing their mother down a flight of stairs or at least of leaving her there, an invalid, once she has fallen); and between parent and child (‘All the same, he [Ranulph] loved his boys. He cast them as princes in the tower as soon as they could toddle. ) Nor is Dora’s name accidental. In another example of ‘writing back’, Carter’s Dora, unlike her Freudian namesake, suffers very little psychic damage from lusting after her father (she ‘fell in love the first time she saw him’) or her uncle, or a string of father substitutes (men old enough to be) with whom she has affairs. The fact that it is the female (sisterly) body which seems most erotic to her (the nape of Saskia’s neck, Nora’s jiggling bottom) is for this Dora a cause for celebration, rather than self-hatred. Her half-sisters, Saskia and Imogen, fare less well in the game of family romance. On hearing her father, Melchior, is about to marry her best friend (another form of incest), ‘Saskia’s wails approached hysteria, whereupon Melchior smartly smacked her cheek…She shut up at once.’ It is because of this betrayal, and her father’s silencing of her anger, that Saskia takes revenge by seducing the couple’s son and her half-brother, Tristram.

Ironically, then, it is the legitimate daughters, Saskia and Imogen, who end up emotionally crippled by their family relationships (though this, perhaps, is a reflection of how rotten the family has become). These weird and troubled sisters might have received greater attention in Carter of an earlier vintage, but here Dora asserts: ‘I refuse point-blank to play in tragedy.’ Perhaps because in dealing with illegitimacy in the past, particularly female illegitimacy, Carter, in her highly wrought and self-conscious work, had sometimes aestheticised pain, even death, now, facing her own, she wanted to face it more squarely or not at all. ‘We knew nothing was a matter of life and death except life and death.’

Dora’s story-telling is a spilling of all the family secrets, bringing the skeletons out of the closet and exposing them to bright lights. This is a comment in itself: no more family secrets, no more lies, no more illegitimacies, Dora seems to assert, yet there is a powerful and unresolved tension in Wise Children between the idea of family secrets and family romance. As the Hazard/Chance family has been shown in the novel to symbolise the broader culture, so too, there is a tension between a desire for openness and equality – a world without secrets or bastards – and the seductive pull of romances from unofficial places, stories from the wrong side of the blanket, form ‘the wrong side of the tracks’.

6. HOW SHE WRITES

Mikhail Bakhtin argues that language is inherently dialogic because it implies a listener who must also be another speaker. It’s a proposition that Carter, the iconoclast, agreed with and tried to illuminate in her writing: ‘A piece of fiction is never static. I purposely try to make what I write open-ended, “user-friendly”’. She demonstrates this in Wise Children by employing a first-person narrator (a form, she said, that men were afraid to use, because it was too revealing). Carter’s mouthpiece, ‘I, Dora Chance’, speaks to her reader as if she expected him or her to reply: ‘There I go again! Can’t keep a story in a straight line, can I?’ At the beginning of the book Dora tells us that she is writing her autobiography on a word-processor on the morning of her seventy-fifth birthday, but the vernacular force of her speech is so great that later she magically appears to transcend the written word, becoming, instead, the old bird who’s collared you in the local boozer:

Well, you might have known what you were about to let yourself in for when you let Dora Chance in her ratty old fur and poster paint, her orange (Persian Melon) toenails sticking out of her snakeskin peep-toes, reeking of liquor, accost you in the Coach and Horses and let her tell you a tale. (p.227)

Dora’s a reader-teaser, endlessly drawing attention to herself by postponing the moment of revelation (‘but I don’t propose to tell you, not now…’) or prodding her reader into paying attention because ‘Something unscripted is about to happen’. She’s also a demythologiser, keen to let her reader in on the tricks of the trade: a chronicler not just of the Hazard and Chance families but of fashion through the ages – talking about brand names, she says: ‘If you get little details like that right, people will believe anything’. As with this last sentence, her gist is always more than surface level, and a huge part of the fun of reading Wise Children lies in seeing how far you can unpack the layers of meaning. How far too, you can unpick the words of others that have been woven into Carter’s/Dora’s own. There is Shakespeare everywhere, but other writers also: Milton, Sterne, Wordsworth (‘If the child is father of the man…then who is the mother of the woman?’), Dickens, Lewis Carroll making an appearance as a purveyor of ‘kiddiporn’, Samuel Butler, Shaw, Dostoevsky (‘My crime is my punishment’), Henry James and Tennessee Williams (‘They lived on room service and the kindness of strangers’) are just a random selection.

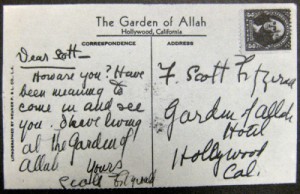

Like any postmodern novel worth its salt, Wise Children not only steals freely from other literary texts but also takes from the texts of other people’s lives and uses these too. In Hollywood, Carter has a field day. Armed, I’d say with the dirt-dishing Kenneth Anger, she has a roster of stars making guest appearances – sometimes as themselves, sometimes in various kinds of drag: featured players are Charlie Chaplin ‘hung like a horse’, Judy Garland (Ranulph’s wife is known as Estella ‘A Star Danced’ Hazard and was ‘born in a trunk’), Busby Berkeley, Fred Astaire and his wife Adele, Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Ruby Keeler, Jessie Mathews, Josephine Baker, Jack Warner, W.C. Fields, Gloria Swanson, Paul Robeson, Orson Welles (‘old buffers in…vintage port and miniature cigar commercials’), Clark Gable, Howard Hughes, Ivor Novello and Nöel Coward (Dora’s and Nora’s first dancing teacher is called Mrs Worthington), Daisy Duck with her missing back molars (it enhances the cheekbones) is a mixture of Lana Turner and Jean Harlow, ending up like Joan Crawford in TV soaps giving ‘good décolleté’. Daisy’s ‘peel me a prawn’ line is Mae West’s ‘Beulah, peel me a grape’ from I’m No Angel, and her Puck, with a ‘face like an old child’, is Mickey Rooney, who starred as Robin Goodfellow in the original model for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Erich von Stroheim is the model for Genghis Khan, the whip-cracking, jodhpured director with a penchant for cruelty and steak-eating orchids, and Dora’s alcoholic, scriptwriting boyfriend, Irish, is an amalgam of many writers – Scott Fitzgerald, Nathanael West and William Faulkner – finally succumbing to the abundant alcohol and indifference doled out in equal measures by the studio system. There’s a veiled portrait, too, of Brecht in Hollywood, whom Dora employs to teach her German and likes because he’s one of the few people she meets out there who aren’t terminally optimistic: ‘What I say is, fuck the bourgeoisie.’

Wise Children has songs, too: music-hall and patriotic war songs, jazz and pop. And good and bad jokes: as well as Carter’s own (‘Why are they called Pierrots?’…’Because they do their stuff on piers’), she pastiches older camp comedians like Frankie Howard and Larry Grayson, and picks up on the more recent Thatcherite humour of Harry Enfield’s ‘Loadsamoney’, turning it into Tristram’s ghastly catchphrase ‘Lashings of Lolly’.

If her sources of material are eclectic, so too is her method of writing – Carter trips lightly through many styles and genres: she is an expressionist who paints ‘a female city, red-eyed, dressed in black’; a magical realist, a student of Hawthorne, Nabokov and Borges, wreathing Perry in magic butterflies; a graffitist scratching ‘Melchior slept here’ across her page; and a montage Surrealist: ‘She was our air-raid shelter; she was our entertainment; she was our breast.’ Carter is a conjuror baiting her audience – ‘All in good time I shall reveal to you how’; a romance novelist who knows where the big bucks are to be found – ‘Romantic illegitimacy. Always a seller’; a teller of tales – ‘If you believe that …’; and wise old wives’ tales. She’s a re-teller of fairy stories – ‘Once upon a time…’/’It had come to pass…’; and autobiographer and ‘inadvertent chronicler’, farceur and tragedian, fabulist and ‘rival realist’ – Sage’s phrase for Carter’s through-the-looking-glass world.

But just as this is a wise book, knowing about culture, history and politics, it is also a childlike one. The house at 49 Bard Road that Dora and Nora live in all their lives is reminiscent of the kind found in English children’s stories. Its large musty room and odd-striking grandfather clock, (mysteriously) absent father and mother, and presiding grandmother left to eke out the rent by taking in strange boarders, are all staples of the genre. Oprhaned children are free children – free of the sexually proscribing authority of their mum and dad, at least, so perhaps the (Wildean) habit of rather forgetfully losing your parents in these stories (as it patently is in Wise Children), is strategic: a way of allowing characters a little more space in which to fashion themselves.

Finally, as well as employing all these styles in her own writing, Carter shows us how a familiarity with many ways of seeing is a part of the modern condition: Dora is not only a passive observer of different genres, she also employs them to shape her own world. She does this to heighten experience, but also self-consciously, even paradoxically, to gain a sense of the constructedness of life by turning people into actors. For instance, when Estella leaves for America she imagines herself in a scene from a movie, and when Melchior, at the age of twelve, absconds from the home of his ‘dour as hell’ puritan aunt, he does so as a character from a children’s story, as Dick Whittington.

7. THE ANXIETY OF PATERNITY

(i) Literal Fathers

The question of paternity arises everywhere in Wise Children. Just ‘what does a father do?’ and ‘what is he for?’, Dora asks. And well she might, given the example of the Hazard men, all of whom disown their children in one way or another. Ranulph leaves his twin sons Tristram and Gareth, fatherless, abandoning them when he shoots their mother and himself in a lovers’ quarrel; Melchior and Peregrine, learning from their father’s example, are equally forgetful about their fatherly responsibilities. Melchior forgets to love his children, and when he remembers, it’s the chilly, arm’s-length affection that the wealthy inadequately bestow on their young. He denies paternity of Dora and Nora altogether, of course – the bastard girls he sired with his landlady one night in Brixton. (Perhaps the reason Grandma creates a romance out of her origins and out of Dora’s and Nora’s is to protect them from their repudiating father, to allow them the freedom of making themselves up rather than being determined by Melchior’s dismissal.) His brother Peregrine, a lavisher of all kinds of love, while watching wistfully after Saskia (and this is ambivalent – are his feeling for her sexual or fatherly?), denies his paternity of both her and her twin sister Imogen.

At the end of this line, Tristram stands no chance as a parent. Not, that is, until his lover, Tiffany, fights back, makes demands upon him, setting down preconditions for his fatherhood. What Carter hints at here is that it is the absence of practising fathers that causes so much grief and confusion: meaning that fathers, having never properly experienced fatherly feelings, often confuse them with sexual ones – hence the tradition of marrying your daughter, of Lears loving Cordelias, in the Hazard family. In the same way, absent fathers are mysterious fathers, which is why these enigmatic creatures become, for their children, the object of such longing and romance.

However, it is the errant behaviour of fathers that creates, among the Hazards and the Chances, so much opportunity for the breakdown of order, for transgression. It seems that in some way fatherly absence is what creates the carnival. That men are such recalcitrant parents stems from their carnival instincts, a sense of narcissism (Peregrine is far too self-involved to be able to give himself permanently as a parent); selfishness (Melchior is more interested in his work than in his children); and a desire not to be controlled or determined within a family order which limits the patriarch just as it confines women.

(ii) Literary Fathers

Such fatherly ambivalence, Carter suggests in Wise Children, might be rooted not only in carnival selfishness but in the anxiety of paternity: the eternal ‘gigantic question mark over the question of their paternity’. It is this forever unresolved uncertainty about their role in biological creativity that has led men to create a mystique around artistic, and especially literary, creativity: as critics like Gilbert and Gubar have shown, the anxiety of paternity translated into the anxiety of authorship. Here, however, Carter seems to be arguing that women, whose role in biological creativity is not in doubt (‘“Father” is a hypothesis but “mother” is a fact’), should now begin to shrug off the male anxiety that they, as writers, have been made to assume, and stop asking question such as ‘Is the pen a phallus?’ Dora does not romanticise or transform sex into something other than it is (which is what men do in their mystifying of the creative process, to cover their feelings of inadequacy); she enjoys it for what it is. A straight-thinking woman, Dora would never mistake a pen for a penis.

8. CARNIVAL GIRLS AND CARNIVAL BOYS

As I suggested above, the Bakhtinian idea of carnival is central to Wise Children. In particular, Carter plays out ideas about sexuality’s relationship to the carnivalesque transgression of order – a transgression that is, according to Bakhtin, at once both sanctioned and illegitimate. Jane Miller has argued in a collection of essays, that because of the breakdown of all barriers, particularly linguistic and bodily ones, that carnival entails, women do not appear in Bakhtin’s work as distinct from men: carnival’s amassing experience, which collapse laughter with fear, pleasure with nausea, where the world become ‘infinitely reversible and remakeable,’ ends up denying female difference. The reason Miller tenders for ‘the inability of even these writers [Bakhtin, Volosinov and other Formalists who are interested in power] to make gender difference and sexual relations central to their work’ is that they are limited by their ‘particular history and their own place in it’. What Carter seems to suggest in Wise Children, however, is a prior problem. It is not just a question of Bakhtin denying difference, denying ‘those pains and leakages that are not common to both sexes’, but that women and carnival might, ultimately, be inimical because female biology and the fact of motherhood make women an essentially connecting force, while carnival is essentially the celebration of transgression and breakdown.

Without entering into the debate about whether transgression can be revolutionary if it is sanctioned by authority perhaps it is in this seeming paradox in Bakhtin’s argument – that carnival’s transgression are both allowed and disallowed – that we can see how well-suited a model carnival is to masculinity, and how ill-suited it is to femininity.

Although some women in Wise Children possess characteristics that might be thought of as carnivalesque, it is a man, Peregrine, who embodies it: he is ‘not so much a man, more of a travelling carnival’. Peregrine is red and rude, a big man and, in the classic Rabelaisian manner, a boundary-buster, growing bigger all the time. To Dora and Nora he is the proverbial rich American uncle, a sugar daddy whose fortunes dramatically rise and fall but who, when he is in the money, spreads his bounty around with extravagance and enjoyment. He is a big bad wolf of an uncle, too, a randy old devil who seduces the pubescent Dora when she is just thirteen. He is a multiple man, and his multiplicity makes him as elusive as the butterflies he ends up pursuing as a lepidopterist in the Brazilian jungle: to Dora and Nora ‘He gave…all his histories, we could choose which ones we wanted – but they kept on changing, so. That was the trouble.’ He is a contradictory presence, a very ‘material ghost’, in whom Dora sees all her lovers pass by as she and he make love at Melchior’s tumultuous birthday party.

If Peregrine’s history is unknowable because he is so multiple, Grandma’s origins are unknown because she refuses to reveal them: ‘our maternal side founders in a wilderness of unknowability’. Grandma arrived in Bard Road at the beginning of the century with no past but enough money to set her going for a year. She is a mystery woman, dateless, nameless, ‘She’d invented herself, she was a one-off’, just as later she invents her family. And like Perry, she is a woman of contradiction, a naturist who happily reveals her naked body to the world, yet speaks with an elocuted voice, a disguise that sometimes slips as she forgets herself and ‘talks up a blue streak’. She and Perry get along famously – they are kindred spirits who joke about the idea of their being married.

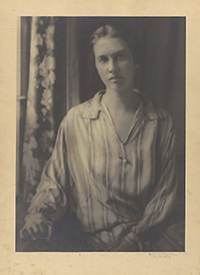

Estella, Dora and Nora’s ‘real’ grandmother, also come close to one of the few descriptions of womanhood in Bakhtin’s work (‘she represents…the undoing of pretentiousness, of all that is finished, competed, exhausted’): Estella’s ‘hair was always coming undone…tumbling down her back, spraying out hairpins in all direction, her stockings at half-mast, her petticoat would come adrift in the middle of the street, her drawers start drooping. She was a marvel, and she was a mess.’ And through her affair with a younger man, Estella is the undoing of Ranulph’s old order. But unlike Perry, who is able to skip away from all his sexual transgressions, Estella is destroyed in the Othelloesque orgy of jealousy and retribution that ensues from her affair.

In the same way, Saskia is a force who wreaks havoc, but like Estella she, too, pays a price. If Saskia’s disruptiveness is carnivaleque, there is little of the carnival’s laughter in her. Saskia’s anger, as it commonly is in women, is directed to the domestic sphere of food and cooking. As a child she’d played a witch in a production of her father’s Macbeth, ‘but she’d shown more interest in the contents of her cauldron than her name in lights’. In later life she continues to be an ‘unnatural’ witchy woman who, rather than nurturing, seems intent upon poisoning people. From the age of five, when she’s seen under a bush devouring the bloody carcass of a swan, to her twenty-first birthday party, when she serves up a duck ‘swimming in blood’, her conspicuous consumption of meat is perhaps some sort of profane attempt to make herself feel legitimate, to be flesh of her father’s flesh. But finally, Melchior’s marriage to her best friend forces Saskia to recognise herself as a terminal outsider and, unable to gain the love she needs from her father, she sets about poisoning him instead. (Conversely, the motherly Grandma, who repudiates men, is an avid vegetarian: ‘she’d a passion for salads, it went with all that naturism. During her strictest periods, she’d make us a meal of cabbage, raw in summer, boiled in winter.’)

The Lady Atalante Lynde, Melchior’s first wife, after falling downstairs (or was she pushed by Saskia and Imogen?), comes to live in Dora and Nora’s basement, and is rechristened Wheelchair in honour of her new invalid status. Once at Bard Road she seems to undergo some sort of transformation: losing her upper-class tightness, she becomes another bawdy, bardy woman, asking a grocer ‘Have you got anything in the shape of a cucumber, my good fellow?’ But her transformation isn’t only psychological. Rather like Flann O’Brien’s bicyclists, or one of Bruno Schulz’s fabulous creatures, Lynde passes through a ‘migration of forms’ – the woman becomes her wheelchair, or at least, they become a part of one another. Welded together they now, like twins, contain something of the other’s personality. After a breakfast of bacon, Dora describes Wheelchair as ‘nicely greased’.

All these women, and Dora too, have elements of carnival in them, but none of them personifies it as Peregrine does. Perhaps this has something to do with carnival’s relationship to order. Carter has argued that in the ‘real’ world, ‘to be a woman is to be in drag’. If in the carnival world, by putting on masks and being other than we are, we transgress the order of the ‘real’ world, then what does this play-acting mean for women who, in the ‘real’ world, already exist in a duplicitous state of affectation? The idea of carnival seems to presuppose a monistic world: the experience of femininity contradicts this, implying that the ‘real’ world is itself a place of diversity, of masks and deception.

We can understand better the idea of carnival being both licensed and illicit if we see how masculinity operates within it. In Wise Children the anarchic solipsism of carnival allows a forty-year old man (Peregrine) to seduce/rape a thirteen-year-old girl (Dora). It could be argued that patriarchy relies upon such masculine transgression of order as a reminder and a symbol of the very force which shores it up. This is what Carter seems to be saying in Wise Children about the function of war in society: that patriarchy legitimates the violent disorders of war in order to sustain itself. Attractive as carnival’s disorder can be to women who have been trapped by patriarchy, when women become the object of this disorder – as they are in war, or in rape, or in ‘kiddiporn’ – then the idea of carnival becomes much more problematic for them, and their relation to it becomes an inevitably ambivalent one: as with Estella and Saskia, carnival is as likely to defeat women as it is to bring down order.

9. BRINGING THE HOUSE DOWN

Nora and I were well content. We’d finally wormed our way into the heart of the family we’d always wanted to be part of. They’d asked us on the stage and let us join in, legit. at last. There was a house we all had in common and it was called the past, even though we’d lived in different rooms. (p.226)

At the end of Wise Children, when Dora and Perry are having sex for the last time (‘you remember the last time just like you remember the first’), Dora fantasises about what it would be like to bring the house down, to fuck it away in some glorious carnival orgy of destruction. She toys with the idea, sensing the excitement of exerting such eradicating (warlike) power. In the end, though, Dora decides that this is not something she wants to do, because although her historical house has sometimes been a painful place to live in, a place from which people have tried to eject her, it is also where her history, her story, lies. Bastard that Dora is, this is a house that she has built too. (That the house is a metaphor for the literary canon is quite clear. Should those left outside trash the house of fiction, or try to renovate it?)

For all Dora’s carnivalesque enthusiasm, and despite her part in conjuring the fantasy world of illusion, of having lived amidst the ‘bruising dew-drops’, she’s always been able to tell the difference between what is real and fake, between what is tragedy (untimely death) and what isn’t (a broken heart). In an interview in 1984 Angela Carter said that she was essentially ‘an old-fashioned feminist’; her preoccupations were with the material condition of women: ‘abortion law, access to further education, equal rights and the position of black women’. On pornography she said: ‘I don’t think it’s nearly as damaging as the effects of the capitalist system.’ Dora, too, is of this materialist persuasion:

wars are facts we cannot fuck away, Perry; nor laugh away either.

Do you hear me Perry?

No. (p.221)

Perry cannot hear Dora because at some level the irrational, possibilising, illusion-making carnivaler cannot entertain the ordered, hard ‘real world’. But just as Dora would not throw away the historical house of order, she would not banish the chaos of the carnival either. Because it seems to her ‘as if fucking itself were the origin of illusion’, and in this carnival world of illusion – in fucking, laughter and art – there is the possibility to conceive of the world differently, to break down the old. There are ‘limits to the power of laughter’ – the carnival can’t rewrite history, undo the effects of war or alter what’s happening on the ‘news’. And there is no transcendence possible in life, Carter tells us, from the materiality of the moment, from the facts of oppression and war. But carnival does offer us the tantalising promise of how things might be in a future moment, if we altered the conditions which tie us down. It is only the carnival which can give us such imagined possibilities, which is why the creative things that make it up in life are so precious: laughter, sex and art.

Dora’s art reports from both sides of the tracks, chronicling a history of exclusion and opposition, but also of wrong-sided exuberance. She ends her story, and her day, with Gareth’s new babies, pocketed deep inside the folds of Perry’s greatcoat (carnival bringing newness into the world). As ever in the dialectical Hazard/Chance family, they turn out to be twins, but this time the old sexual divisions are broken, for this latest double-act signals a change of direction – these wise children are ‘boy and girl, a new thing in our family’. And who knows where such a strange combination might lead? With this challenge, Angela Carter signed off. Leaving the reader, in the best Bakhtinian fashion, holding the babies. But if we attend, we can hear her out there riding Dora’s wind: ‘What a wind! Whooping and banging all along the street…The kind of wind that gets into the blood and drives you wild. Wild.’ Listen, wise children, can’t you hear her shouting to us: ‘What a joy it is to dance and sing!’

Notes

1. Spring 1993

2. Angela Carter, Wise Children, Vintage, p.19.

3. If this seems rather to schematising a response, then I call in my defence Carter herself, who often iterated the idea that she intended her fiction to have direct political meaning: ‘My characters always have a tendency to be telling you something’ (Omnibus, BBC1, 16 September 1992); ‘in the end my ambition is rather an eighteenth-century “Enlightenment” one – to write fiction that entertains and, in a sense, instructs’ (Contemporary Writers: Angela Carter, Book Trust for the British Council, 1990); ‘I believe that all myths are products of the human mind and reflect only aspects of material human practice. I’m in the demythologising business’ (Angela Carter, ‘Notes from the Front Line’, in Michelene Wandor [ed.,], On Gender and Writing, 1983).

4. Omnibus

5. ‘All art is political and so is mine. I want readers to understand what it is that I mean by my stories…’ (unpublished interview with Kate Webb, 15 December 1985).

6. Martin Amis, Other People, Penguin, 1981.

7. Angela Carter, ‘Notes from the Front Line’.

8. Salman Rushdie, ‘Eating the Eggs of Love’, The Jaguar Smile, Picador, 1987.

9. Interview with Mary Harron: ‘I’m a socialist, damn it! How can you expect me to be interested in fairies?’, Guardian, September, 1984.

10. Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism, Chatto & Windus, 1993.

11. Foucault makes this argument in many of his works. It is a particularly strong theme of Discipline and Punish, Penguin, 1975, and The History of Sexuality, Volume One, Penguin, 1976.

12. Omnibus.

13. Contemporary Writers, Book Trust.

14. Carter gets the wheel of fate into the novel by having Tristram spin a wheel (of fortune) on his S/M game show.

15. This is an idea which permeates all of R.D. Laing’s work, but is the cornerstone of The Divided Self, Pelican, 1965.

16. It would take another full essay to delineate all the Freudian and Shakespearian connections in Wise Children. Here, I am just trying to indicate the extent to which they penetrate the novel.

17. Angela Carter died of cancer on 16 February 1992.

18. Mikhail Bakhtin’s work on carnival is to be found in Rabelais and His World, Indiana University Press, 1984; Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, Manchester University Press, 1984; and The Dialogic Imagination, University of Texas Press, 1981.

19. Contemporary Writers, Book Trust.

20. There is a pub called the Coach and Horse on Clapham Park Road, equidistant from where Angela Carter lived in Clapham and the road where we might suppose that Dora lives in Brixton. Not Bard Road, of course (this is Carter’s invention), but Shakespeare Road, which – with Milton Road, Spenser Road and Chaucer Road – runs off Railton Road. It is also just over from Brixton Water Lane, the street known traditionally for providing digs to the theatrical profession (it is here that Marilyn Monroe’s chorus girl lives in the film The Prince and the Showgirl, 1957). Railton Road was the heart of the area known as the ‘Front Line’ before the riots of 1981 and 1983, after which Lambeth Council knocked down half of it. When, later in the novel, Dora says she prefers the heat of Railton Road at half-past twelve on a Saturday night to the freezing country house of Melchior’s first wife, she is both making a political statement – choosing the culture of the colonised over that of the empire-builders – and talking about the relative culture of these two groups. At Lady Lynde’s house she is offered lousy food and a cold bed. On a Saturday night on Railton Road, Dora would have found blues parties, drugs, booze and many other people who felt ‘What a joy it is to dance and sing!’. [The rather tatty Irish pub, The Coach and Horses, is now called The White House ,and had been turned into a fancy nightclub with bouncers at the door and stretch limos in the street. – KW 2009]

21. Kenneth Anger, Hollywood Bablyon, Straight Arrow Books, 1975. [No doubt Angela was aware that Anger played the Indian prince in Max Reinhardt’s 1935 Hollywood version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream – the inspiration for the one she writes about here. – KW 2009]

22. Contemporary Writers, Book Trust.

23. Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic, Yale University Press, 1979.

24 Jane Miller, Seductions: Studies in Reading and Culture, Virago, 1990.

25 ibid.

26. ibid.

27. I’m thinking here of the New Historicist writing on Shakespeare, and of Linda Hutcheon’s A Theory of Parody, Methuen, 1985.

28. Bruno Schulz, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, Picador, 1980.

29. Omnibus.

30. Interview with Mary Harron.