Graeme Macrae Burnet, Case Study. Saraband – TLS

“The tarmac of the path glistened like ink. I imagined stepping into it and slowly sinking up to my waist.” If you need any reminder that Graeme Macrae Burnet is a writer who revels in metafiction there is plenty of evidence in Case Study, his tortuous, cunning and highly self-conscious new novel, filled with doubles and dopplegangers. Readers who equate self-referentiality with literary integrity, or who simply enjoy being toyed with, are in for a treat.

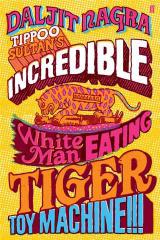

Burnet has always wanted his readers to think about who is speaking in his fiction, and to separate his own life from those of his characters. For this reason, his books are framed in elaborate ruses involving manufactured versions of himself, which remind us that, in fiction at least, charlatanism often points the way to truth. In the two published volumes of his Detective Gorki trilogy (The Disappearance of Adèle Bedeau, 2014, and The Accident on the A35, 2017) Burnet presents his texts as “translations”, while in his Booker prize-shortlisted His Bloody Project, (2015), a certain “G.M.B.” alleges he “came across” the documents that comprise the bulk of the novel in an archive. Now, in a preface to Case Study, “G.M.B.” returns to tell us that the diaries on which this work rests were sent to him in response to a “blog post”. And sure enough, you can find a blog by Burnet on Goodreads, where he claims to have “unearthed” works by one A. C. Braithwaite, a 1960s “enfant terrible” and the author of “Kill Your Self” and “Untherapy”.

Braithwaite is one of two adversaries in Case Study, a psychotherapist described in the press as “Britain’s most dangerous man”. The other, doing battle with this charismatic philanderer in the time-honoured manner, is a young, isolated and unworldly woman. She adopts the pseudonym “Rebecca Smyth”, the first name after Daphne du Maurier’s heroine, the second an affectation to make her seem more plausible when she first arrives at Braithwaite’s shabby office, disguised as a “nutter” and asking for treatment. It is she who imagines herself “sinking [in] ink”, and her diaries record her posing as a patient to discover if Braithwaite’s menace extends to murder, or at least if his therapy is responsible for her sister’s death. “Suicide makes Miss Marples of us all”, she observes after the sister kills herself following a session with Braithwaite. “One cannot help looking for clues.”

The clues come thick and fast, though many are concealed in an updated “Strange Case of” story, which reimagines the traditional game of cat-and-mouse between detective and criminal as one between a therapist and patient. This allows Burnet to deliver a riveting psychological plot, rooted in the therapeutic counterculture of the 1960s, that keeps overturning ideas about madness, identity and culpability. The air of indeterminacy is deepened by Braithwaite’s encounters with two of the Sixties most charismatic iconoclasts: the radical ‘anti-psychiatrist’ R. D. Laing, and Colin Wilson, who reframed existentialism for British readers with his work of literary criticism, The Outsider (1956). Braithwaite’s egotism, though, overwhelms his admiration for the men, making him boorish and violent. Eventually, he is ejected even from this camp of intellectual outcasts.

Braithwaite certainly thinks of himself as an outsider, hailing from a Northern, puritanical family who fail to understand his unorthodox thinking. But unlike “Rebecca”, whose waywardness is met with criticism and chastisement, once he arrives at Oxford, his nonconformity is understood as a sign of genius. By the time he reaches bohemian London, his iconoclasm fits right in. Here he mingles with Joan Bakewell, Princess Margaret and the closeted actor Dirk Bogarde, who announces that it’s “fine to be your own doppelganger”. This sums up Braithwaite’s philosophy: there is no such thing as authentic identity, he argues, everything is manufactured by “family, decorum and responsibility”, so why not play around with different personae?

What is so smart about Burnet’s novel, and the source of much of its humour, is the introduction into this permissive environment of “Rebecca”, the mousey homebody who ends up outwitting the so-called genius. In a text that runs parallel to her diaries, “G.M.B.” presents Braithwaite’s biography, supplying ample evidence of the therapist’s fraudulence, conceit and misogyny. And yet nothing is straightforward: contradictory accounts defy easy judgement, as do the abundant clues, hinting, crucially, at what is missing from Braithwaite’s solipsistic analysis – the social and cultural forces that shape behaviour.

As time passes, the macho guru figure falls from fashion, while Rebecca’s strident individualism – promising a path to female emancipation – looks increasingly prescient. But in the 1960s, when suicide by women reached its peak, the problem of finding a feasible female identity was immense. As if to indicate that something is wrong with the model of freedom “Rebecca” tries to enact, and the more dominant the proto-Thatcherite side of her becomes, the more she behaves like a split personality. Soon her strange conduct pushes us to question her sanity. Sitting in Braithwaite’s waiting room she obsesses over a tear in the wallpaper, and during one session with him she pulls a mouse wrapped in tissue from her handbag. She thinks of ending her life by walking into water with “stones in her pocket”. And, of course, the place where this all happens is Primrose Hill.

“I have rather been toying with you”, “Rebecca” announces in a postscript, and these literary allusions (to Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap, Roland Barthes’s “tissue of quotations”, the suicides of Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf, the “Mad Woman in the Attic” stories of du Maurier, Woolf, Charlotte Brontë and Charlotte Perkins Gilman) all add to that sensation. But Case Study is more than a work of power play. For all the author’s distancing techniques he still pulls the reader into his tale, leaving us with ink on our hands, too. This is a sign not only of our immersion, or “sinking”, in literature, but of the way Graeme Macrae Burnet’s crafty text demands that each reader confront the madness in us all.

This review was published in the TLS on 8.10.21 as ‘When Charlatans Lead to Truth’.