Sontag’s Distinction – TLS

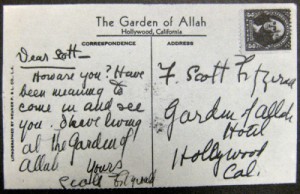

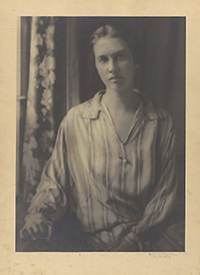

“Susan is here – what a beauty she is! But I dislike so much about her, the way she sings girlish and off key, the way she dances, rhythmless and fake sexy…” In her 1957 diary, Harriet Sohmers recorded her ambivalence about the arrival of Susan Sontag in Paris. “She seems so naive. Is she honest?” They had met originally in 1949 in a San Francisco bookshop, beginning an affair while Sontag was still a teenager. Nearly a decade later, after Sontag had married and given birth to a son, the relationship resumed. Sontag was studying philosophy at the Sorbonne; Sohmers, the translator of Sade’s Justine, was working nights at the New York Herald Tribune. For Sontag, who spent much of her childhood living near the desert in Arizona, the international, bohemian scene she became part of in France was critical in the formation of her sensibility. Here she kept company with radicals, aesthetes and homosexuals, and spent her nights roaming from cafe to cafe, eager for the conversation this mix of people created. She was introduced to the revolutionary ideas of the nouveau roman and nouvelle vague and became a passionate cinema-goer, often seeing two or three films a day.

Sontag had studied in California, Chicago, Harvard and Oxford, but it was in Paris that she shook off her American parochialism, escaping the elitism of many of its postwar intellectuals. Giving free reign to her enthusiasm, she became a connoisseur of the kitsch, outré, obscure and avant-garde. At the same time she began to read experimental postwar French literature and, influenced by expatriate friends in Paris, those writers she took as her exemplars: Beckett, Borges, Kafka and Nabokov. In so doing she found the work of a lifetime: crusading against the distinctions that divide high from low culture, form from content, thought from feeling, ethics from aesthetics, or fantasy from judgement (distinctions she felt, which should only be employed “against themselves”); and making connections between literature, film, theatre, opera and art, in many of which she also practised. As she wrote in her diary in the first flush of her relationship with Sohmers, “everything matters” – a sentiment reinforced in the 1960s when her lover, Jasper Johns, told her the same thing.

Part of what drew her to Johns and his friend, John Cage, was that they shared not only her wide interests but also her feeling that in a time of capitalist excess these might be best expressed in an art of restraint, in what Sontag called an “aesthetic of silence”. Much as she admired this, though, her own writing grew from “restlessness and dissatisfaction”: she would not be quiet or sit still. Instead, she translated her lively curiosity into a very un-American devotion to the past (where she pointed out, so much of “everything” happened). She also championed those writers who grew outside capitalism’s domain: a relationship with Joseph Brodsky in the 1970s was influential in shaping her view of the romanticism of the American left when it came to communism, and in making her think more deeply about writing as part of global culture, leading to essays on ‘The Idea of Europe’ and ‘On Being Translated’, as well as eulogies to Marina Tsvetaeva, Danilo Kiš and Witold Gombrowicz. From this flowed a renewed concern for writers around the world battling against authoritarian regimes. In 1978-9, at the time Salman Rushdie was placed under a fatwa, she was chair of American PEN.

Now, a decade after her death in 2004, we have two new biographies. Daniel Schreiber’s presents a portrait of the intellectual-as-celebrity and is much concerned with image, reputation and Sontag’s response to fame (it was published first in 2009 under the title Geist und Glamour). Jerome Boyd Maunsell’s book is more centrally engaged with her work in the context of the life. While Schreiber regards Sontag with suspicion, is disposed to see any rethinking as evidence of dissembling, and claims to have “clarified… dishonesties”, Maunsell presents such changes of mind more judiciously as a facet of her intellectual mobility, a writer returning to and elaborating themes. Schreiber gives us a sense of how Sontag appeared to others, making use of interviews with friends and colleagues; Maunsell relies more on published material to inform his exegesis, including Leland Poague’s invaluable interview selection, 1995, and the two volumes of diaries edited by her son, David Rieff, 2009, 2013.

If their designs upon her life differ, for both biographers the bones of her story are the same. What Sontag called her “desert childhood”, lonely, isolated, and fatherless, left her with a world-hunger she was determined to satisfy. As she observed, something about her “eccentricity or the oddness of [her] upbringing” served her well: it meant she escaped the pressure other girls felt to limit their desire. As an adolescent, discovering a bunch of Modern Library paperbacks in a Hallmark card store, she read them voraciously. When the family moved to California she engineered a meeting with Thomas Mann. Still only sixteen, she enrolled on Chicago’s Great Books of the Western World course, the following year marrying Philip Rieff, a sociology lecturer – a hastily-begun relationship that unravelled slowly and painfully: “I lost a decade”, she said later. Once she made her way to Europe though, as well as living in England and France, she journeyed across Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece. “I haven’t been everywhere, but it’s on my list”, she quipped. Places she could eventually cross off included Morocco, where she paid court to the Bowleses; Cuba, Vietnam, China and Poland (later decried, Schreiber notes, as trips to the “Disneyland of revolution”); Israel, to film a documentary about the 1973 Arab-Israeli War; Bosnia, where she staged a production of Waiting for Godot during the siege of Sarejevo; and Japan, to which late in life she kept returning. As a young woman Sontag vowed: “I shall anticipate pleasure everywhere…I shall involve myself wholly”. But later diaries reveal she was not immune to the problem of female appetite. She was suspicious of her avidity, concerned her collecting and discarding of people was vampiric: “Gathering my treasure, I learn what they know…then take off.” Love affairs with men and women were not uncomplicated. The relationship with Sohmers was certainly turbulent, and Sontag was crushed when she read her diary. At the end of 1958 she moved back to America, divorced Rieff, and took her young son to New York to begin the life she had always envisaged for herself: that of freelance intellectual.

Sohmers’ assessment was to have a profound effect, leaving Sontag with an insecurity she found hard to dispel. Perhaps she sensed something in the casually devastating remarks that went beyond sexual gaucherie or a perceived failure to be hip, reflecting more broadly on her viability as a writer and thinker. In America, as if to repudiate Sohmer’s slur, Sontag challenged the old-guard intelligentsia by publishing provocative, epigrammatic criticism not only in Commentary and Partisan Review but, more fashionably and democratically, in Vogue and Mademoiselle. Sontag’s readers admired her intellectual rigour but also thrilled to the cutting-edge critique in her work, much of it concerned with desensitizing and cultural over-production. There were seminal essays and monographs on underground gay sensibility (‘Notes on Camp’, 1964), “the intellect’s revenge upon art” (‘Against Interpretation’, 1964), voyeurism, surveillance and the spread of imagery (On Photography, 1977; Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003), and the unthinking use of metaphor (‘On Style’, 1965; Illness as Metaphor, 1978; AIDS and its Metaphors, 1989). She soon became one of the country’s most fêted and public intellectuals, photographed by Cartier-Bresson, filmed by Andy Warhol, the subject of devotional artwork by Joseph Cornell. Yet the suggestion that she was “off key”, “naive”, not quite credible, lingered, if only in the conditional praise that habitually came her way. Typical of this genre was Jonathan Miller’s designation of Sontag as “the most intelligent woman in America”.

The American critic Vivian Gornick has argued that what she made of such ‘praise’, and her experience of the dubious distinction conferred upon her as a “remarkable exception”, should provide the organizing principle of any biography, helping us to better understand the position of the female intellectual in the twentieth century. Certainly the authoritative style of Sontag’s early writing, her lofty public manner and her reluctance to discuss her sexuality, all seem like strategies to deflect from her gender and help her assume the mantle of universality and exemplariness routinely accorded to great male writers. But, as Schreiber reports, it was a stance that left some feminists angered by her apparent lack of partisanship. In 1975 Adrienne Rich demanded in a letter to the New York Review of Books that she make clear her position on feminism. Sontag’s furious response was that of course she was a feminist, but this did not mean she would succumb to intellectual banality or bow to “infantile leftism”. The criticism continued, however: in 1994 Camille Paglia argued that Sontag’s “cool exile was a disaster for the American women’s movement.”

Her aloof style also reflected a distaste for the confessional. Any biographer has to labour under the particular difficulty Sontag presents as a subject, one with a deep-set antipathy to the idea of biography or to searching for underlying meaning – something that had its roots in her earliest intellectual discoveries. Her marriage was not entirely “lost”: she spent much of it co-writing a book with her husband on Freud (though in their divorce settlement she agreed not to be credited). Maunsell points out that an early chapter, ‘The Tactics of Interpretation’, anticipates Sontag’s later themes: “for Freud, nothing is ever allowed to just be what it is. ‘Slips of the tongue, pen, memory; mislaying of objects; fiddling or doodling…the most ordinary trivialities may become symptomatic, meaningful.’ One thing is always substituted for another by Freud…yet with how much accuracy?” Though Sontag played down the influence of the nouveau roman on her early experimental novels (The Benefactor, 1963; Death Kit, 1967) – and Maunsell, following this, places them rather intriguingly as works of American surrealism – it’s hard to imagine that her thinking about Freudian displacement was not consolidated when she read the French postwar writers, with their dislike of metaphor and its insinuation of ultimate meaning. She writes in ‘On Style’ that “metaphors mislead”, an idea that surfaces again and again. In a 1978 interview with Rolling Stone she observes, “what was perishable in a lot of writing was precisely its adornment…the style for eternity was an unadorned one.” Indeed, much of Sontag’s work forms a commentary on the tendency in modernity to excess, to critical duplication or recycling. “We live in a world of copies”, she protests, “the work is not allowed to remain itself”.

Sontag’s public manner may have been provocatively cool, but her style in criticism tended, as Maunsell notes, “to revelatory explication and ardent admiration”. Often referred to as the High Priestess or Dark Lady of American Letters, her ardour made her seem to some, girlish – another epithet frequently applied to her (Daniel Mendelsohn reviewing her Diaries, spoke of her “girlish effusions”; Stephen Koch interviewed in the New York Observer, thought her “very girlish”; Philip Lopate in Notes on Sontag (2005), describes her “great girlish squeal”); she herself worried that ardour could overwhelm its object. In an essay on Elias Canetti, she wrote that for “talented admirers…it is necessary to go beyond avidity to identify with something beyond achievement, beyond the gathering of power.” Her declared aim in writing, after all, was self-transcendence, and while “ardent admiration” could arouse the energies necessary for criticism, there was a danger that bold identification with a person or work might result in attention being directed back to the admirer’s taste or talent in admiring.

Perhaps all this accounts for Sontag’s fascination with the figure of the collector, someone who transforms admiration and appetite into discrimination and connoisseurship, yet remains caught – in Maunsell’s phrase – in “the pathos of avidity”. He is present in her first novel as the self-absorbed Hippolyte, collecting his dreams in order to better understand himself; and in her penultimate novel, The Volcano Lover, 1992, in the character based on William Hamilton. “Does he seem cold? Is he simply managing, managing brilliantly…He ferried himself past one vortex of melancholy after another by means of an astonishing spread of enthusiasms. He is interested in everything.” Women, Sontag suggests are not able to move past their own abjection in quite the same way. In the novel, Hamilton recalls a fable about a statue of a woman. A man ‘collects’ her, granting her a limited consciousness with the sense of smell. (“Impossible to imagine the fable with a woman scientist and…a statue of the beautiful Hippolytus”, Sontag observes.) For her, every odour is good, because every odour is better than none. All her pleasures, then, are tinged with loss: she cannot make the “luxurious distinction” between good and bad. “She wants, if only she knew how, to become a collector.”

Schreiber’s concentration on Sontag’s public persona goes some way to describing how the desert girl was able to translate her passionate will to knowledge into one of the most vital canons in America’s recent cultural history. He pays particular attention to her polemical interventions: her contention at the time of the Vietnam War that the white race had created nothing which could compensate for its violence; her chastising of the American left at a 1982 Solidarity rally for not realising that “communism was fascism with a human face”; and, in the aftermath of 9/11, her “bemoaning the absence of discussion worthy of a democracy”. This is balanced by a good deal of gossipy detail, such as Sontag, amused at the role-reversal, when Warren Beatty keeps her waiting for a date while he primps himself in the bathroom. Schreiber’s treatment of her work, though, gives too much leeway to its reception, quoting without challenge many barbed and negative reviews. And his suggestion that Sontag not only succumbed to her image, but was so self-deceived as to be incapable of distinguishing between the bad and the good in herself, seems particularly self-serving, justifying the role he too often falls into as biographer for the prosecution.

Maunsell, by contrast, presents a nuanced account of Sontag’s intellectual development. He traces her ever-present subjects, above all the duty of the writer to direct attention, while seeing that her books arose “out of self-correction” and self-contestation, the result of a continuing “readiness to immerse herself in contemporariness”. Indeed, the achievement of Maunsell’s biography is how intelligently he makes sense of Sontag’s responsiveness to the contemporary, and the currency this gave her work for over half a century – a period long enough for her to repeatedly modify arguments or reason on the contrary. She was an oppositional writer, and the opposition was frequently wielded against herself. Understanding this, Maunsell champions her “crucially misunderstood” early novels, judged as failures in realism rather than on their own terms as Duchamp-like “endlessly reconstructable puzzles”, designed to resist analysis. But he also writes persuasively about a lecture delivered not long before her death when she defended the novel form precisely for its “artful sense of completion”. “Now”, Maunsell observes, “it was not interpretation that was the main danger for her”, but “the untrammelled flow of information.”

In learning how to become a collector – one with the freedom to make new distinctions and then change her mind about them – Sontag had to develop a style of her own. As a young woman she relished the freedom and authority of impersonality in her writing, but over time it suited her less, the “freedom”, unable to accommodate what she wanted to say. It took her thirty years to find a way of speaking more directly, with “warmth and candour”, as Maunsell puts it, “to learn” as Sontag herself said in interview, “how to write a book I really like: The Volcano Lover”. The book she liked was the one in which finally she reflects on just what that earlier style suppressed: “I had to forget that I was a woman to accomplish the best of which I was capable. Or I would lie to myself about how complicated it is to be a woman. Thus do all women, including the author of this book.”

A slightly different version of this review appeared as ‘From desert girl to Dark Lady’ in the TLS on 23.1.2015.